Juan Mascaró: The Mallorcan Voice Behind the Bhagavat Gita’s English Soul

In the spiritual journey of Mahatma Gandhi, the Bhagavad Gita was a constant companion—”the one book he always carried.” Its verses offered him solace and strength, especially during his imprisonments. Decades later, a man from a quiet village in Spain would render those same verses into English with a lyrical grace that continues to resonate. That man was Juan Mascaro.

orn on December 8, 1897, in Santa Margalida, a rural village in Mallorca, Mascaró grew up among almond groves, olive trees, and the golden light of the Mediterranean.

His early years were steeped in Catholic tradition, but a youthful discovery of a book on occultism awakened a deep spiritual yearning. From this unlikely intersection of rustic Spanish life and metaphysical curiosity began the inner journey of a man who would eventually translate from a language not his own (Sanskrit) into another language not his own (English).

Despite growing up in a Catalan- and Spanish-speaking environment, Mascaró excelled in English early on. He worked at the British Consulate in Palma and caught the eye of financier Joan March, who helped fund his studies at the University of Cambridge. There, Mascaró immersed himself in English literature and oriental languages, particularly Sanskrit and Pali. It was an ambitious intellectual undertaking, yet it was also deeply spiritual. To Mascaró, translation was not merely linguistic—it was devotional. As he would later write, “If life or action are the finite and consciousness or knowledge the infinite, then love is the bridge that turns life into light.”

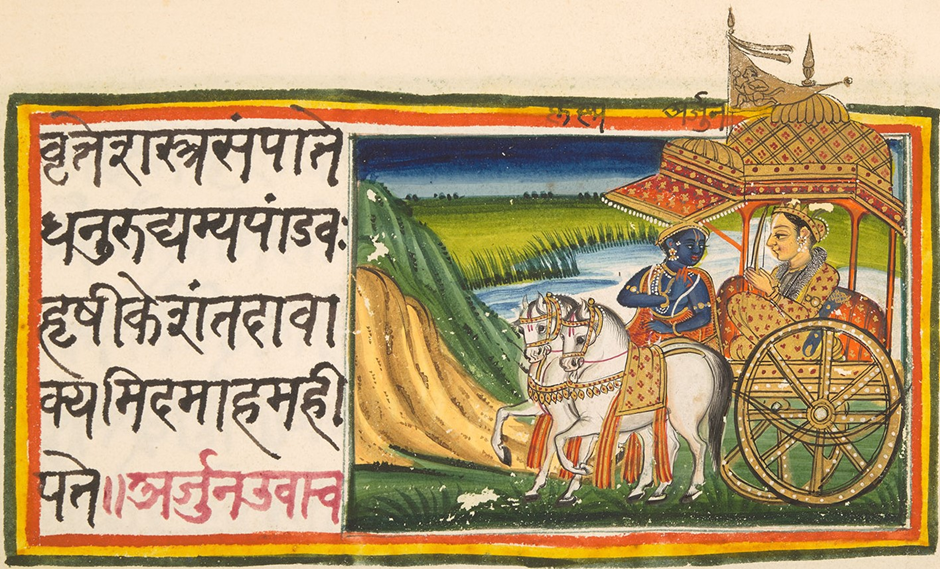

His most famous work, the English translation of the Bhagavad Gita, was published by Penguin Classics in 1962. It had taken him two decades to complete. Unlike many literalist translators, Mascaró sought to capture the spiritual and poetic rhythm of the original text. Verse 9.26 held particular meaning for him: “The one who offers me with love a leaf, a flower, a fruit, or even a little water, I accept that offering made with a pure heart.” To Mascaró, this was not just poetry but a core spiritual principle—that small, sincere acts done in love carried infinite value. He often said that he hoped his translation had been faithful not only to the spirit of the Sanskrit but also to his own heart.

Mascaró’s versions of the Upanishads (1965) and the Dhammapada (1973) further cemented his legacy. His translation of the Upanishads brought Indian metaphysical philosophy to English readers in prose that retained its mystical resonance. He emphasized the phrase “tat tvam asi”—”you are that”—as the essential message: that each soul is of the same divine light. He believed this consciousness could transform how we treat each other. “When you stand before another person, to know ‘you are that’ is to know you can never raise a violent hand,” he wrote.

Mascaró also compiled a collection titled Lámparas de Fuego (“Lamps of Fire”), bringing together sacred writings from the world’s religions. To him, the mystical truths of Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism were not in conflict but facets of the same eternal light. As Jon Kobeaga wrote in Diario de Mallorca in 2024, Mascaró “discovered in the study and analysis of India’s classical texts that which is interwoven like light, love, and life.” Kobeaga emphasized Mascaró’s belief that the smallest act, if performed with a pure heart, could become a spiritual offering—echoing the Gita’s message and revealing Mascaró’s own essence as a translator not just of words but of truths.

Kobeaga also noted how Mascaró saw Sanskrit not merely as an ancient language but as a vibrational medium, with sounds that connect to the divine and origins rooted in eternity. This understanding informed every line he wrote, from his translation of the Gita to his rendering of the Upanishads. His spiritual approach was inseparable from his poetic craft.

And yet, his luminous intellectual life was shadowed by personal sorrow. His son, Sebastian, died young, a loss from which Mascaró never fully recovered. Though he remained in Cambridge—living in Comberton, surrounded by books, notebooks, and gardens—his later years were marked by grief and reflection. Still, he continued to translate, write, and quietly teach. His diaries reveal a man who saw his vocation as sacred. In the spring of 1958, he wrote: “These lamps of fire may become a light in the deep darkness and a refuge in the storm. For in the wonder of these great words, we find goodness and beauty; and beyond the truth of ideas, we find the Truth of our being.”

Mascaró passed away on March 19, 1987. The New York Times obituary honored him for having “achieved the unique feat of translation from languages not his own into another language not at first his own.” He had, through devotion and extraordinary empathy, become a bridge not only between East and West but between the finite and the infinite.